Limestone reliefs of a man and woman, each thick-armed and hardy—allegories of Louisiana’s economic pillars of agriculture and industry—towered over Pat Reed and Zora Olsson as they walked up the steps to the Capitol Annex Building. In the lobby, they signed in with the security guard and glanced upward at a sweep of murals that, in their Depression-era depiction of a square-shouldered working class, were a complement to the limestone figures on the exterior. In vivid color, the figurative paintings clustered together all the tenderness and toil that builds a society: a young man in a pilot’s cap eyes a toy plane taking off into some future that promises success for hard work; a team of construction workers pushes and pulls a massive steel beam, the realization of new construction; and a makeshift clinic puts the skills of doctors and nurses within reach of a rural community.

Reed and Olsson broke their gaze from the seventy-five year old mural and headed upstairs to then Lieutenant Governor Jay Dardenne’s office.

**

“I wasn’t hopeful they would find a way to restore it,” said conservator Robert G. Lodge in a matter-of-fact, even-tempered tone that seemed at one with the steady hand required for his line of work. In 2009, sent in by the Office of Cultural Development mere days before a wrecking ball collided with the hurricane-ravaged Regional Mental Health Center in Algiers, Lodge and his crew from McKay Lodge Fine Art Conservation Laboratory freed a fifty-foot-long glass-and-marble tesserae mural by mid-century artist Conrad Albrizio from the face of the building where it had resided for over forty years. Neither the massive removal nor the handling of Albrizio’s work was a first for Lodge. “This was our third [handling] of an Albrizio mosaic,” said Lodge. “We specialize in preservation for [this era] of art.”

The Lodge’s staff prevented the mural’s pieces from dislocation by applying adhesive facing before it was cut into four-hundred-pound sections to make transportation possible. The process produced ten panels, with the building’s bricks still attached to the back. Each section was loaded onto an eighteen-wheeler and brought to a warehouse provided by Kevin Kelly, well known as the owner of Houmas House Plantation and Gardens.

Pictured: In 2009, the Albrizio mural was removed from its original site and placed in donated warehouse space, where it remained for four years before funding was secured for its restoration. Photo courtesy of McKay Lodge Fine Art Conservation Laboratory.

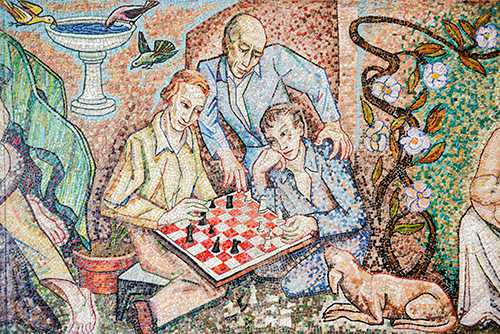

This 245-square-foot mural (unnamed, according to Curator of Visual Arts for the Louisiana State Museum system Dr. Richard Anthony [Tony] Lewis), created in 1963 for the Mental Health Center, employed Albrizio and five assistants over the course of five months. The subject matter reflects the many ways families can care for the mental wellness of their children through play and education. The mental health facility was one of nine operated by the state at the time and specialized in the psychiatric care of children. A testament to Albrizio’s craftsmanship, the mosaic weathered Hurricane Katrina remarkably well, but the building did not.

For four years, the mural would rest, face down, with a dermis of bricks slumbering on top. When in New Orleans for business, the Ohio-based Lodge would visit the warehouse to check in on the artwork like a doctor assessing a patient in a coma. “It was really impressive,” he said. “We have art critics to articulate why; but I’ve seen a lot of Albrizio’s work, and this was quite distinct and unique … I just wasn’t sure there would be the finances to restore it.”

**

Conrad Albrizio. The name alone conjures up early twentieth-century generalizations about German stoicism and Italian romance, which, in its most benign form, is a good mix for an artist who lent images to the socialist ideals of the New Deal era. New York born, Albrizio traveled back and forth from New York City and New Orleans early in his adulthood as he studied architectural drawing and painting. According to the John Shelton Reed title Dixie Bohemia: A French Quarter Circle in the 1920s, Albrizio was an early member of the Art and Crafts Club in New Orleans and founder of the New Orleans Art League. He briefly enrolled in the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris and traveled to Rome and Fontainebleau to study fresco. These experiences would form the current that carried Albrizio from painting portraits in his bohemian studio in Orleans Alley to adorning the walls of Huey P. Long’s expanding dominion and that of his gubernatorial successors.

In 1931, Albrizio was commissioned to paint murals over several hundred square feet for the then newly constructed State Capitol, according to art historian Carolyn Bercier. Though only one of the five murals created at this time survives—you can see it in the Governor’s Press Room—this work was the catalyst for multiple public projects by Albrizio which could be found in the Louisiana cities of Gretna, New Iberia, Shreveport, DeRidder, Houma, and New Orleans as well as Alabama. In fact, during his tenure as an art professor at LSU from 1935 to 1954, he created five murals funded by the Works Progress Administration as well as the epic execution of a fresco for the Waterman Building in Mobile, Alabama, which, according to Bercier, took Albrizio and an assistant thirteen months to complete.

The technical skill and creative focus required to author any of these pieces would be reason enough to hail Albrizio as one of Louisiana’s most impressive artistic (adopted) sons, but it is the common thread of humanity—depicted as industrious as it is exhausted, as fertile as it is forsaken—that make his public work so evocative. One example of this duplicity is the rather dispassionately-titled mural segment “Activities of South Louisiana” in Shreveport’s Louisiana State Exhibits Museum, where the placid gaze of a maternal and robust woman, open-armed, seems to contrast sharply with the adjacent scene of African American laborers whose expressions alternate from strain to determination. This juxtaposition of struggle and peace is a refrain in Albrizio’s work.

**

“We needed a project,” Zora Olsson, the state registrar for the Louisiana State Society Daughters of the American Revolution, stated with modesty as if debating between taking up macramé or needlepoint. Rather, the $300,000-plus, two-year project that she and Pat Reed embarked on after leaving Lt. Governor Jay Dardenne’s office would amount to more than a crafty distraction; it would be a monumental rehabilitation of one of the state’s most treasured artworks.

“When we instated a new state regent, we decided to take on a new [initiative]. Pat and I just happen to live in a city where we can take a meeting with the Lieutenant Governor to figure out what that should be,” Olsson chuckled, at the advantages of being a Baton Rouge-based member of the three-thousand person state organization. The Daughters of the American Revolution, one of the largest women’s organizations in the U.S., aims to support historic preservation, education, and patriotism; undertaking the restoration of a state-owned mural that depicts the joys of parenting fit squarely into that mission.

“Lt. Governor Dardenne informed us of the mural, and we embraced the project right away. The entire state membership voted on it, and when it passed we started raising money,” Olsson said. “Pat, our state recording officer, wrote her first grant ever, and we were awarded the highest amount given by the national society: $10,000.”

Several individual contributions and fundraisers later, the money LSDAR raised statewide was pooled with funds from the Percent for Art Program, a legislative mandate that applies 1% of the cost of state building construction to the acquisition of public art. At last, the dismembered mosaic, for years entombed in Kevin Kelly’s warehouse, was shipped to Lodge’s workshop in Ohio. The doctor would finally get to awaken his patient.

Over the next few months, Lodge’s team slowly chipped away the old brick, sanded off the original grout, and revealed the reverse, or underside, of Albrizio’s mural. After removing the facing, each section was affixed to an aluminum panel with a honeycomb interior. This construction method ensured that the mural would be fully supported, yet light enough, that future transport wouldn’t pose the same problems. “This job was particularly difficult,” Lodge revealed, “because we could not build a support for the back of it [at the beginning]. We had to work in reverse.”

Every small stone had to line up perfectly, and those tesserae that had fallen away throughout the reconstruction process, or in the many decades before, were painstakingly replaced. “If we had the original pieces, we’d place them back in; if not, we’d try to find similar mosaics in the same material, and if that wasn’t possible we would make our own,” he said.

After a lengthy and labor-intensive process, the mural was loaded back on the semi and returned to Louisiana. At the advice of Lodge’s company, the mural found a home away from the elements, inside the Capitol Park Museum in Baton Rouge. On September 21, 2015, Lt. Governor Jay Dardenne, Chief of Staff Cathy Berry, the Office of Cultural Development, and LSDAR unveiled Albrizio’s fifty-foot mural, unseen by Louisiana citizens for over six years.

The immense stretch of this richly-hued evocation of familial love is cast with a mother pointing out the stars in the night sky to daughters by her lap, fathers playing chess with their progeny, and young children communing with nature and indulging their imaginations. The assembly of the work is exquisite, the narrative is powerful (especially given where it used to reside), and having the opportunity to walk up to it and linger in the details is a gift. “We all attended the dedication ceremony. I lost count of all the people,” said Olsson. “It was the first time any of us had seen the mural up close, in person. It’s just an incredible work.”

That overhead mural that had greeted Olsson and Reed on their initial visit to the Capitol Annex building, itself an Albrizio, now seemed like a celestial body charting the way home for its sister artwork. Pat Reed enthusiastically agreed: “Thanks to the hard work of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Louisiana Office of Cultural Development, this beautiful Albrizio mosaic is now home to stay.”