Photo courtesy of Terry L. Jones

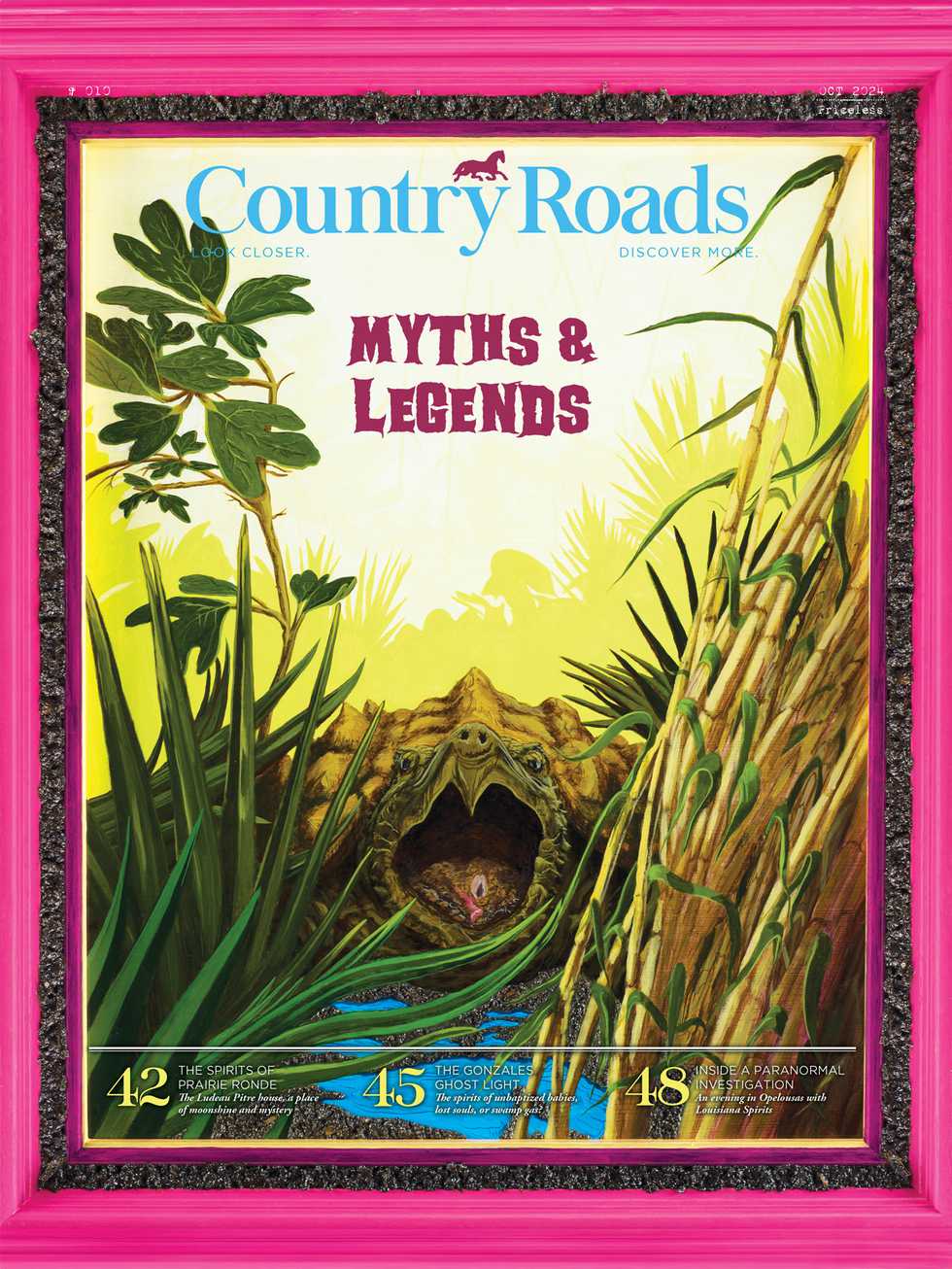

The author (on right) with park personnel and volunteers dressed for a living history program.

I was twenty-nine years old in 1981 when I became the first manager of Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Commemorative Area in Natchitoches. At the time, I was pretty naïve about how the Louisiana government operated; the job was quite an eye opener.

One surprise was discovering that the state civil service test, which is designed to make sure hirings are based on merit and not cronyism, could be manipulated. Certain state employees (such as park managers) were required to take the civil service test. When a job opened up, the top ten scores were submitted to the hiring agency, and it could pick anyone from those ten names.

I later learned that if the agency wanted to hire a specific person, it could reject the top ten scores and request the next ten. This could be repeated until the agency received the ten scores that included the person it really wanted to hire.

This loophole could even have been used to hire me, but I never found out if that was the case.

I also learned to tread carefully around politicians. Not long after starting my new job there was some sort of controversy involving the fort (I honestly don’t remember what the problem was), and someone mentioned that Rep. Jimmy Long might have to get involved. In my youthful exuberance I smugly declared that the park was my responsibility, and I was not going to have a politician interfering with it.

My comment was quickly passed on to Long, and a couple of days later I got a call from the chief of operations in Baton Rouge demanding an explanation. After hearing me out, the chief informed me that all state legislators took a great interest in what went on in their district’s parks (not to mention controlling our budget) and that I needed to smooth things over with Mr. Long.

Scared that my job might be on the line, I confided in my mom and discovered that she was a big Jimmy Long supporter. He was a part of the famous Winn Parish Long family and still had close connections to our area. Mom said Jimmy was a really good legislator and that I needed to make things right with him.

A couple of weeks later, I went to see Long at his Piggly Wiggly store in Natchitoches. Instead of being confronted by a ticked off politician, however, I found myself sitting before a very courteous and friendly man. Contritely, I explained that I had meant no disrespect but, being new to the job, was simply trying to establish my authority. Long said he understood, assured me that there were no hard feelings and thanked me for coming in.

Then, with a slight smile, Long said, “You know, I approved you for this job.” I didn’t know it at the time, but it was customary for state officials to consult legislators before filling certain positions in their district. Long said he approved me because he liked the fact that I was a Winn Parish boy who was getting a Ph.D. in history. I then told him how my mom was one of his loyal supporters, and we parted on good terms.

Interestingly, I left the fort three years later to join the faculty at the Louisiana School for Math, Science and the Arts. Jimmy Long was one of the school’s founding fathers and introduced the legislation that created it. I don’t think he involved himself in the hiring of individual faculty members, but I’m sure a whisper in the ear of certain people could have derailed my hiring if he had so wanted.

In addition to learning to be respectful of local politicians, I also came to realize how wasteful the state government can sometimes be. In my annual budget, everything was compartmentalized. There was an x-amount of money for gasoline, repairs, equipment, miscellaneous items, etc., but the money could not be moved around.

We were trying to start a living history program and needed to buy a lot of period clothing and historical knickknacks to put in the fort, but there was little money earmarked for that in the miscellaneous account. On the other hand, I had several hundred dollars each year to buy tires for our truck—a brand new truck that wouldn’t need new tires for some time.

I complained to my district manager, Wick Pickett, and asked if I could request that no money be earmarked for tires the next year and, instead, add that money to the miscellaneous account. Wick said no and explained that each year’s budget was based on what was spent the previous year. If I didn’t spend my tire money one year, that category would be eliminated and there’d be no money for tires when I needed them.

Wise in the ways of the budgetary process, Wick advised me to never end a fiscal year with money left over in any account. Spend it all, he said, because if there was a surplus, my budget would be reduced by that much the next year.

So, in order to satisfy this quirky accounting necessity, I spent hundreds of dollars every year on things I really didn’t need. By the time I left, there was a utility room stuffed with new tires.

Dr. Terry L. Jones is a professor emeritus of history at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. An autographed copy of “Louisiana Pastimes,” a collection of the author’s stories, costs $25. Contact him at tljones505@gmail.com