Photo by John Kemp

Alan Flattmann prefers to paint a New Orleans that is unspoiled by modern industrialization.

Alan Flattmann is a master painter who has traveled the world painting images of lovely, ancient cities in Italy, Ireland, Croatia, Mexico, and on the Isle of Crete. Yet, he is constantly drawn home to New Orleans, where, since the early 1960s, he has found his art in its streets and alleys, along the riverfront, in the smoky glow of flambeaux torches in a Mardi Gras night parade, and in the aging-but-graceful architecture of the French Quarter.

There is a reason why Flattmann and other artists have such passion for the city and its environs. This semi-tropical extension of the Caribbean world is, as novelist Walker Percy once described, a city adrift in a high tide of American culture. When Flattmann paints the city landscape, it is like having a conversation with an old friend. His paintings are reminders of what Tennessee Williams once wrote in A Streetcar Named Desire: “Don’t you just love those long rainy afternoons in New Orleans when an hour isn’t just an hour—but a little piece of eternity dropped into your hands?”

Flattmann’s paintings of the city’s iconic streets and landmarks create narrative images of place and time. They call to mind the impressionistic paintings of William Woodward, whose paintings of the Vieux Carré a century earlier heightened public awareness of the city’s architectural heritage and helped launch a preservationist movement that saved many of the Quarter’s most historic buildings.

Like Woodward, Flattmann is part of a long tradition of landscape painting in Louisiana that emerged over a century ago. Although a few landscape artists worked in New Orleans before and during the Civil War, the rise of the so-called Bayou School of landscape painting began shortly after the war. Its most important artist was the French-born Richard Clague, who was known for his dark and romantic landscapes of rural Louisiana. Others following Clague’s lead were Marshall J. Smith, Jr., William Henry Buck, Paul Édouard Poincy, George David Coulon, Harold Rudolph, Charles Giroux, and Alexander Drysdale and his ever popular dreamy and impressionistic paintings of bayous and live oak trees. This romantic realism in Louisiana landscapes persists to the present day despite the coming and going of various modernist movements in art during the twentieth century; today’s artists sense the same ironies, historical presence, timelessness, and place that have motivated artists for generations. Yet, they—like Flattmann—are creating their own visions of the Louisiana landscape.

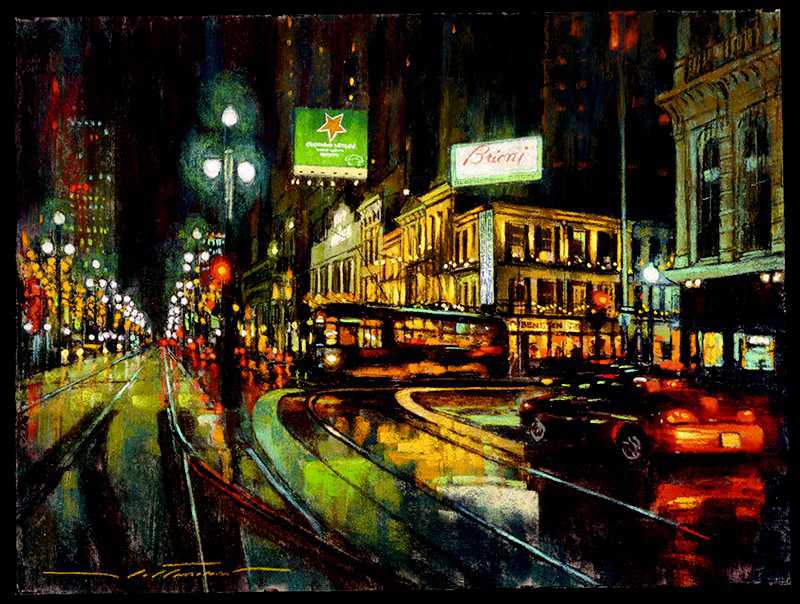

Left:“Into the Night.” From “An Artist’s Vision of New Orleans: The Paintings of Alan Flattmann” with text by John R. Kemp, © 2014 Alan Flattmann and John R. Kemp, used by permission of the publisher, Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.

Left:“Into the Night.” From “An Artist’s Vision of New Orleans: The Paintings of Alan Flattmann” with text by John R. Kemp, © 2014 Alan Flattmann and John R. Kemp, used by permission of the publisher, Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.

New Orleans has always been the center of Flattmann’s art. Whether he is painting in a café, on a sidewalk, or in his studio, his style seems effortless. “The act of painting is what gives me a reason for existence,” he once said, reflecting upon the space that art occupies in his life. “If for some reason I could no longer make a living from painting, I don’t know what I’d do.”

Flattmann’s career began in the early 1960s at the famed John McCrady School of Art in the French Quarter. Initially, he thought he might pursue a career in commercial art but changed his mind once he understood the power of art. “Painting something pleasing to the eye has a great deal of satisfaction,” he recalled years later. “A painting can be emotional as well as beautiful. When I discovered that my creations could have an effect on other people, and that they were pleased or they felt the experience that I put down on canvas, that is when I knew what and why I wanted to paint.”

During those formative years, many artists influenced his work, especially the Mississippi Regionalist painter and founder of the school of art that Flattmann attended, John McCrady, who gained some fame in the 1930s and 1940s. A student of Thomas Hart Benton, McCrady stressed a classical training in art, especially drawing. He was a superb teacher, gathering around him many young artists who went on to successful careers. Others also left their mark on Flattmann. Names such as Rembrandt, Whistler, Sargent, Manet, Innes, Constable, Corot, and Degas rolled off his tongue as he explained the lessons he learned from the masters. “I liked the way Whistler worked with paint, the way he scraped his colors down and added color back again.”

Until 1968, Flattmann’s exposure to art had been limited to art history books, magazines, and exhibitions at the New Orleans Museum of Art. That year, he visited the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. “I walked into this room of Rembrandts; I flipped out,” he recalled. “Rembrandt created a reality within that canvas that has a life of its own. You can live in them, breathe in them. I then realized how powerful a statement a painter can really make. All those impressions had a big effect on me and the way I work. They became my hero figures, not great politicians or great soldiers, but great artists.”

Like many other young art students at the time, Flattmann earned extra money on Jackson Square, painting quick pastel portraits of passing tourists. After completing art school, he wanted to do serious work. At first he painted French Quarter street scenes, decaying nineteenth-century buildings, and tradespeople and workmen along the riverfront and in the Old French Market. And in 1967, he returned to McCrady’s now and then to teach classes. After McCrady’s death the following year, the young artist continued to teach there until the school closed in 1983.

The more Flattmann painted in the French Quarter and rural South Louisiana during the late 1960s and early 1970s, the harder he searched for scenes unspoiled by the modern industrialization that was quickly changing the landscape. Sugarcane harvesting is now mechanized, and knife-wielding cane cutters are almost a thing of the past. Gangs of longshoremen and roustabouts, once common along the Mississippi River docks, have given way to forklifts, shipping containers, and other more efficient ways to unload cargo vessels.

His fascination with nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pre-industrial New Orleans drew him to the Caribbean. In 1973, with glimpses of Winslow Homer’s exotic nineteenth-century West Indies burned into his imagination and a large grant in hand, the twenty-seven-year-old artist and his wife, Becky, were off to Barbados in search of a New Orleans and South Louisiana lost to the modern age. The cane fields, the plantations, and the fishermen who pulled in their nets by hand recalled a rural South Louisiana from fifty years earlier. That fascination with antiquity continues to this day.

Flattmann’s Vision of New Orleans (Pelican, 2014) and his earlier book French Quarter Impressions (Pelican, 2002) reveal a lifelong flirtation with the city where he was born in 1946. “It really struck me around 1996 that I had always used the Quarter as a fallback, but it really had a deeper meaning to me. I was always looking for this grand subject and realized that it was under my nose all along. I was painting around it but resisted painting the Quarter by itself in fear of being called a French Quarter artist.” He views his paintings of the city as visual documents, recording people, places, and things perhaps as he would like to see them. It is a place that is constantly changing and not always to his liking. Recalling those days in the 1960s when he was an art student in the Quarter he once said, “There was excitement in the air back then. Unfortunately, it has lost a lot of its character. Today, for example, part of the old farmers market is a flea market. It is the same flea market you’d see in Mexico or some parts of Europe. It doesn’t have any New Orleans character to it at all. That’s lost, and that’s a shame.”

Over the years, Flattmann’s skills have made him a major national figure in the world of pastel painting. He conducts workshops throughout Europe, the United States, Mexico, the Caribbean, and, most recently, China. In addition to his many awards, his paintings have appeared in juried art shows throughout the world. His work, featured in numerous regional and national publications, can be found in hundreds of private and corporate collections as well as at the Butler Institute of American Art, New Orleans Museum of Art, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Oklahoma Arts Center, Longview Museum of Art, Mississippi Museum of Art, and Lauren Rogers Museum of Art.

When Flattmann talks about his work, however, awards and honors rarely enter the conversation. He likens his painting to writing poetry: “I am more a poet than a storyteller. With vocabulary, a poet creates a symphony with words. I’m working with subject matter that really exists. Yet, I paint them in a way that I can use my vocabulary of paint, canvas, and composition in such a way that I’m making a lyrical statement about it. I’m drawn to painting things that are not necessarily beautiful in the sense of a beautiful sunset or beautiful woman. I’m drawn to things I find have a sense of peace, of contentment, a sense of mood. That’s what I’m trying to do with my painting.”

John R. Kemp writes about Southern artists for various regional and national magazines. His most recent books are “An Artist’s Vision of New Orleans: The Paintings of Alan Flattmann” (upon which this article is based) and “A Unique Slant of Light: The Bicentennial History of Art in Louisiana” (co-author, co-editor).