Photos by Jeremiah Ariaz

A young rider gains instruction in the saddle. Cecilia, Louisiana. June, 2015.

“When you take care of your horse, it will treat you right,” Joe Andrews said, a lesson he shared with his son, Arsenio. “You can tell which riders don’t take care of their horses when you get out there on the trail.”

The trail Andrews refers to is a dusty, mostly unpaved road that winds through seas of sugar cane fields in Torbert, Louisiana, a small farming community in unincorporated Pointe Coupee Parish just a few miles east of Livonia. Throughout the year, Joe and Arsenio travel across Louisiana to join trail rides down similar roads—each one hosted by multiple horse-riding clubs—alongside hundreds, sometimes thousands, of other riders.

The trail in Torbert that Joe and Arsenio were about to travel was hosted by “Lock & Load,” a horse-riding club based out of Brusly, Louisiana, located on the west bank of the Mississippi River. It is one of many rides that take place every weekend. Hundreds of riders convened at the trailhead, taking cover under whatever shade was available on that sweltering Sunday in late July. Father and son fed and groomed their horses before saddling them and hopping on for the ride, which began three hours behind schedule once riders and logistics were eventually coordinated.

Leading the pack was a roofless school bus filled with young children and booming, bouncy zydeco tunes that could be heard a mile away. A rented porta-potty was strapped to its back end. Scattered among the bus and the unorganized clutches of horses were small pickup trucks, four-wheelers, and golf carts, some filled with ice cold beer and water bottles tossed up and down the mile-long line of thirsty travelers, from cart to cart and horse to horse.

Trotting through the hot dust of the trail and the shade of the sugar cane, the riders inhabit a world where trail rides are no longer borne of economic necessity; but the gatherings are also more than just a party. For riders such as the Andrews, both members of the “Wealthy and Rogue” riding club in Opelousas, the trail is a place where values are instilled, memories built, and wisdom extended to future generations.

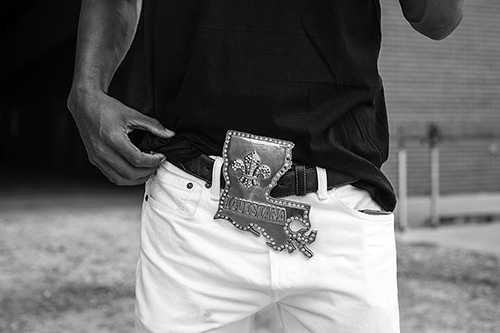

Louisiana belt buckle, Semien Stables. Sulphur, Louisiana. April, 2015. Jeremiah Ariaz.

Joe and Arsenio, separated by a generation, are at the forefront of a long line of riders dating back nearly three hundred years, when the trail ride was less about having fun and more of a routine job. The trail rides are part of a continuing legacy of horsemanship that began in the vast swathes of South Louisiana’s grasslands during the eighteenth century among les gens de couleur libres or “the free people of color,” according to Conni Castille, the producer of T-Galop: A Louisiana Horse Story, a documentary that details Louisiana’s equine culture. As far back as the 1730s, these early riders traveled on horseback under the supervision of their white owners, from New Orleans to trading posts in Opelousas and Attakapas (present day St. Martinville) to assist with purchasing cattle. Rather than travel back to the city, these early trail riders were given partial autonomy, leaving them in this wilderness to look after their herds of livestock and to establish permanent relations with the area’s Native Americans and cattle traders. This semi-autonomy, along with the mixture of African, Native American, and European cultures, formed the genesis of Louisiana’s Creole community, or le monde creole. Despite its origins in involuntary servitude, most participants today will say that trail rides are all about tradition, a source of community-building and a tap into a deep well of cultural heritage that draw horses and riders down Louisiana’s country roads for weekends filled with home cooking, zydeco music, and family.

Friends and family accompany the ride in a pick-up drawn trailer onto which one rider moves from his horse. Jeanerette, Louisiana, 2015. Jeremiah Ariaz.

There is no telling how many riding clubs exist in Louisiana. In the Baton Rouge area alone, there are anywhere between fifty and two hundred depending on who you talk to. Some of the larger clubs with big budgets boast dozens of members and broadcast their annual trail rides with big zydeco headliners like Lil Nate or Chubby Carrier and the Bayou Swamp Band. Some of the smaller clubs, comprising only a handful of members, have no official listing, just a club T-shirt and a few horses.

Mike Pete, in attendance at the “Lock & Load” ride, recalled his grandfather’s stories about rides into the headlands and through the sugar cane fields. Back then, they used to camp out, cook, and race horses on the “bush tracks,” Pete said. “That’s how they all kicked it off years ago.”

That was back when trail riding really began to take more of a social shape, explained Pete, also the club president of the “Crazy Hat Riders” in Lafayette. It wasn’t long after when the horse clubs began turning trail rides into weekend-long festivals, he said. Nowadays, you don’t have to own a horse or even live in the country to enjoy the trail ride. In his forty years of trail riding, Pete has helped numerous riders purchase and care for horses. The inclusiveness is a good thing, he said, though there is some distinction to make between the weekend trail riders and those maintaining the stables.

Every day, Pete heads out to his barn in Breaux Bridge. His horses are fed twice a day (in the morning and at night), washed and groomed two-to-three times a week, and wormed about every two months. “If I go to the barn and I can saddle a horse and ride, it’s like me and my horse become one. I relieve a lot of tension when I’m at the barn,” he said. “Sometimes I don’t ride. Sometimes I just go to the barn and groom the horses and play with them.”

When he can’t make it to the barn, his boys, fourth-generation trail riders—ages 10, 13, and 14—take his place. “The culture is still there. I love the way my sons like it,” Pete said.

Father and son ride in a custom-built chariot. Jeanerette, Louisiana, 2015. Jeremiah Ariaz.

After a couple of hours of sweating it out on the trail, the riders in Torbert flip the bus around and trot back to base camp. The smell of cracklins and jambalaya and the sound of live zydeco greets them. The final day of the trail ride is nothing less than a feast filled with live music and dancing. “You gonna meet some nice people; you gonna meet some wild people. They could just first meet you and they gonna act like they been knowing you,” Pete said. “I never meet a stranger.”

About the Photographs

While riding my motorcycle in rural South Louisiana, I encountered a large group of people riding horseback. They commanded the road, and I pulled over for them to pass. I retrieved my camera from the saddlebag of my bike and took a few photographs as they rode by. A gentleman near the end of the procession waved, encouraging me to join. So began my ride with the African American trail-riding clubs.

I grew up in Kansas and had a particular image of a cowboy shaped by popular culture. They were gruff, serious, white, and situated in the West. For the past ten years, much of my artwork has deconstructed such images and the mythology associated with the American West. The trail riders in Louisiana are a stark contrast to most depictions of cowboys, offering a radically different vantage point to consider images of the West and acknowledging that black equestrian culture stems from a time when the American West was Louisiana territory.

Since March of 2014, I have been photographing weekend trail rides across Louisiana. I’m drawn to the mix of rural and urban sensibilities, the sound of zydeco, the smell of the horses and hay. Everyone I’ve met has been incredibly warm, generous, and welcoming; I hope to build a body of work that reflects the people and the spirit of the rides. —Jeremiah Ariaz

Additional images can be viewed at jeremiahariaz.com.