Kourtney Zimmerman

My friend Ross Baringer is a kayak swamp tour guide for New Orleans Kayak Swamp Tours. He likes to tell his tours—mostly made up of folks from other states and countries—that you can get pretty much anywhere in South Louisiana with a boat. He’s not entirely sure of that, but it’s his favorite theory.

I called him one day in December, with the dead brown of winter beating down upon all life in the Colorado mountains where I now live, looking for a thaw.

“You caught me on a good day for that,” he said, and told me about his plan to kayak a hundred miles from Ward Creek, deep in the suburbs of Baton Rouge, to Lake Pontchartrain.

There is a thin line between rigid over-planning and idealistic under-planning, where adventure is allowed a necessary freedom, to spill over its banks, flood the plains, and run away with itself. To go into a trip like this having anticipated every detail is less of an adventure, more of an exercise. We wanted to survive, but we did not want an exercise.

After three months of planning, I boarded a plane to New Orleans with my Hennessy Hammock tent, two headlamps, a lightweight sleeping pad, plenty of wool socks, and an army blanket. Ross had planned the finer details of our route on Google Earth, and we scheduled our friends and family for water resupply points. Finally, our last night on dry land came. Neither of us had ever really done anything like this before, and as that began to dawn on us, we didn’t sleep much.

Day One: Ward Creek to Bayou Manchac to Amite River

At around 6 am on an overcast Monday morning in March, Ross’s dad drove us and our boat trailer from New Orleans to Ward Creek at Barringer Foreman. We spent an hour packing the kayaks—this being the first time we packed our kayaks, we didn’t know if all our gear would fit. Lacking a drybag big enough to store all our food (summer sausage, crackers, powdered matcha, cheese, Jameson…), I had improvised a complex system of heavy-duty garbage bags. Two, because if one got punctured or wet, we’d have the other one. I probably should have put a third one on.

I knew that Ward Creek and Bayou Manchac flood with Baton Rouge’s litter every time a heavy storm comes through. It’s a problem that hasn’t yet been solved at the source, and at the time we paddled through, it appeared exacerbated by the massive river flooding in the area only months before. We saw tattered plastic sheeting caught in tree branches high above our heads. We passed many backyard boat launches ripped from their bolts, mangled more with each passing thunderstorm, dangling and rotting.

Then there were the “trash nests,” as I came to call them: large swaths of household items and garbage caught in downed branches—they appeared every quarter mile or so. Footballs, Big Gulps, styrofoam chunks, bits of plastic toys. The undocumented details of peoples’ lives, things I imagine most people don’t want to remember losing. Up on the banks, we occasionally saw large appliances—stoves, dryers, refrigerators—either dumped there long ago or flooded out months ago. Likely some of both.

One of the trickier things about camping on a river in South Louisiana is that it’s hard to tell what’s land and what’s mud.

Even so, with the gray velvet clouds blocking the sun, the scene was eerily beautiful, like we were floating past the debris of a great catastrophe.

We reached the Amite River after about five solid hours of paddling. Our first stop came in late afternoon, at a little biker bar called Whiskey River at Port Vincent. We were greeted by a spirited dog (we later learned that his name is Whiskey) who followed us into the bar.

A few drinks and some flood stories later, we ambled back to our kayaks for a few more miles. We had to find a place to camp for the night. We found an unoccupied island in the middle of a riverfront “neighborhood” of sorts, and we drunkenly set up camp for the first time—tied up our hammocks, strung up our food bag in a tree, and talked through twilight. The night sounds of wild Louisiana built into a chorus as we sat in a tree and waited for the bugs to come.

They did not come.

A cold quest

They didn’t come because the temperature dropped to an unlikely 40 degrees plus Louisiana humidity. I was barely prepared for the cold snap and I still woke up with a few numb toes, but Ross hadn’t brought a blanket. He didn’t sleep that night.

After a morning of rowing, we made it to Manny’s Bar in Maurepas just in time for free pulled pork sandwiches. The bar was full of folks playing pool and drinking Bud Light. We happened to sit next to a compassionate off-duty bartender, who offered to give Ross a blanket if we could get to her house on a stretch of river a few miles off our route.

[You might also like: Highway 16]

It took half the afternoon to get to the riverside neighborhood to look for “a white dock with two pirate flags,” and we spent another hour slowly paddling up and down the channel. Nobody had pirate flags. We were about to head back to the Amite when we passed a lady wandering around in her backyard.

“Do y’all have any gas? I’m trying to mow the lawn but I ain’t got no gas,” she said. We looked down at our kayaks.

“No,” Ross said. “But do you have a blanket?”

“Y’all got a couple bucks?” she asked, raising her eyebrows. I had five bucks.

And with that, we had a quilt heavy and big enough to get Ross through the coming night.

“Well, maybe we’ll get eaten by alligators then,” I said. “It would be a good way to go, right?”

With the sun already disappearing, we landed on a thin patch of land next to a road. A motorboat with two grumbling anglers trolled slowly next to the bank as we strung up the hammocks; one was yelling at the other, telling him how much he didn’t know about fishing, which I knew from experience was a tradition among fishermen. Though they seemed occupied enough with their tasks, I kept catching them stealing glances at us as we set up camp, and they slowly drifted closer to our bank as the sun went down. We went to sleep soon after dark, hoping we weren’t on the wrong side of the natives floating around us.

In the wilderness

We entered the least populated stretch of the Amite the next day. Herons, cormorants, hawks, and bald eagles warred with each other above our heads. We met cypress trees, bigger and older than any on Ross’s tours. There were parts of that day when we knew we could yell without being heard by a single soul. That day, Ross told me he should have been an ornithologist; I told him he could still be one.

We lost track of time, which is apparently the right thing to do, because we paddled fifteen miles that day, putting us half a day ahead of schedule. We were due to meet my dad for a water pickup near the town of Maurepas the next day at noon, and we were close to that pickup point when we stopped to pitch camp in the wildest place either of us had ever slept.

Kourtney Zimmerman

One of the trickier things about camping on a river in South Louisiana is that it’s hard to tell what’s land and what’s mud. Such was the case in the lagoon we pitched camp in that evening, and I guessed that no one had set foot on that muddy root system in a long time.

We kept our boots on as we pitched our beds, and I found it appropriate to pull out the plastic water bottle full of Jameson in my backpack. We traded pulls as the sun climbed down the trees behind us.

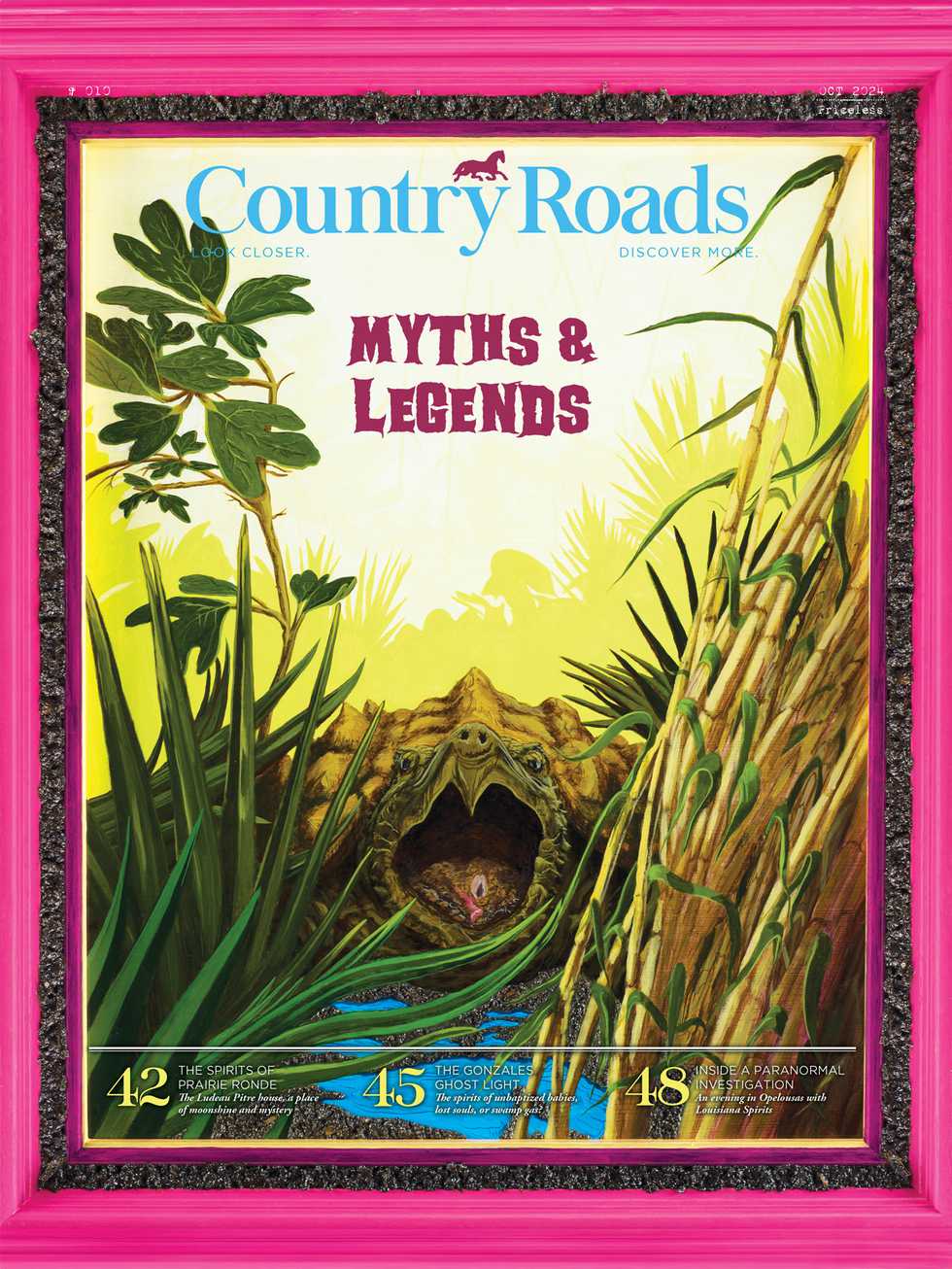

About an hour after we siphoned our nicely-buzzed selves into our hammocks for the night, Ross mumbled over in a queasy voice, “Are we gonna get eaten by alligators?”

“What?” I said. “No.”

“We’re strung up like alligator food right now. They’re more active at night, and I keep hearing things in the water, just wondering what your thoughts are,” he said, as if ending a memorandum.

“Well, maybe we’ll get eaten by alligators then,” I said. “It would be a good way to go, right?”

ìOne of the trickier things about camping on a river in South Louisiana is that itís hard to tell whatís land and whatís mud.î

At around 2 am, something woke me and I peeked out of the mesh, driven by fear and excitement. The moon was bright enough to cast shadows. I could see everything; every tree and splash, the Amite through the trees, shining. And the noise: the frogs and crickets and roaches and beetles, all the creatures of the night, louder and closer than I’d ever known them to be, drowning out the hum of Highway 22 in the distance.

After so many years of living in this place—after leaving, thinking I had a pretty good idea of the wilder parts of the state—here I was, somehow in a place I had never been before; a place few people at all had ever been before. And in my head, a whisper: this place is so special.

It’s much more effective to feel such a thing out here—with reptilian mouths full of sharp teeth, howling around you, smelling your blood and deciding on a whim not to indulge—than to be told so by another person.

We both woke up at sunrise for the first time on the trip.

“Did you see the moon last night?” I asked.

“Oh my God, did I,” said Ross.

That’s all we said; words ruin things like this.

The last stop

We beat my dad to the pickup point. I gave him a hard hug he probably didn’t understand, then we were off to Lake Maurepas. Just around the bend, we counted how many alligators could’ve eaten us the night before. Most were small, but goblin-like, with all the striking details that spit fear in the hearts of mortals.

[Now read: Assimilation Wetlands]

The plan was to camp at the edge of Lake Maurepas where the Amite River pours into it, but that plan dissolved with the banks around us. We’d be stringing the hammocks up over water that night, above an entire Atlantis of alligators.

The horizon opened up and the wind intensified, and there was Lake Maurepas, an ocean when you’re in a kayak. We took it in, sat in silence for a moment before coming to the obvious conclusion: we wouldn’t be able to cross it with that wind, and this is where our adventure had to end.

It could have felt like a defeat had we taken it that way, but the four miles back to the launch felt more like a victory lap. I relieved my arms of the mission on the last mile or so, letting my vessel go where it wanted to, swirling with the deep river.

I looked up at the birds in the treetops and noticed that every muscle in my upper body ached with satisfaction. Was this what the birds felt every day of their lives? Not the sensation of getting somewhere, but of going, of just moving forward—of following a path that sprawls out in front of them, by way of wind, luck, and strength? Is it so simple, to just go?

Perhaps.

This article originally appeared in our May 2018 issue. Subscribe to our print magazine today.