Photo by Erika Goldring, courtesy of Voodoo Music and Arts Experience.

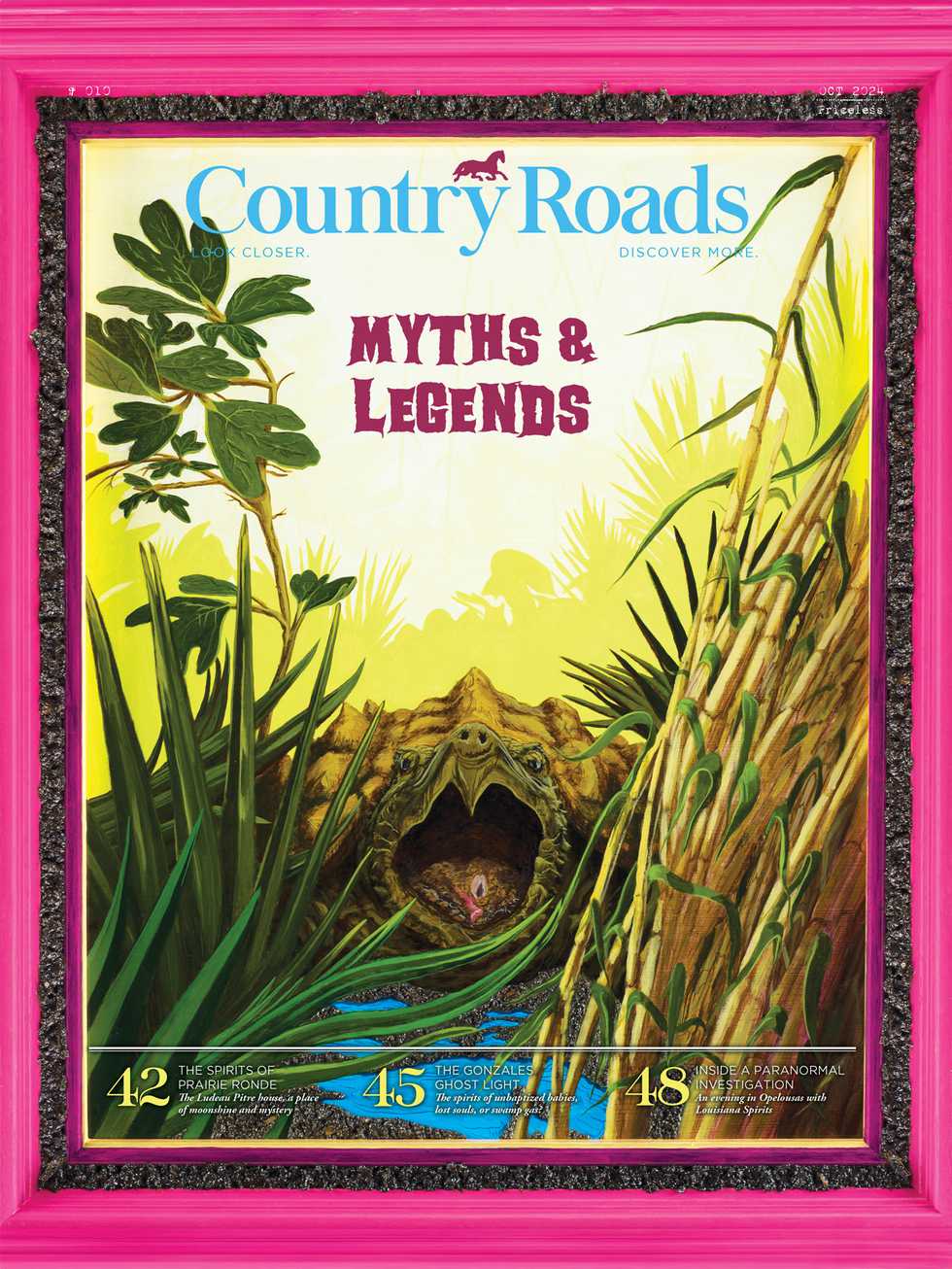

Live entertainers are having to come up with alternative avenues for performance. In July, Voodoo Music and Arts Experience hosted a drive-in, socially-distanced concert series featuring The Revivalists (pictured), Tank and the Bangas, and Galactic.

Six days after David Bowie died in January of 2016, I found myself second-lining in the French Quarter, singing along to his chart-topping 1983 single “Let’s Dance” with my then-new friend, Beth, and hundreds of brightly-costumed strangers as Arcade Fire bandleaders Win Butler and Régine Chassagne led the packed procession from Preservation Hall. Just two days before, members of Arcade Fire and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band had announced they would celebrate Bowie’s life and legacy in the traditional New Orleans fashion. So we went, and ended up elbow-to-elbow with Butler’s hot pink jacket and red megaphone, following the brass band’s unmistakable sousaphone like a guiding beacon. By the time the throng of fans and spectators arrived at One Eyed Jacks on Toulouse Street, so many people had gathered that NOPD had to disperse the crowd for traffic to resume. It goes without saying, and for that reason is worth reiterating, that this sort of thing doesn’t happen everywhere.

In Louisiana, live entertainment certainly plays a fundamental role in our economy, but its contributions go beyond attracting robust tourism revenue. Here, the performing arts are woven into our collective cultural identity in ways more permanent and prominent than anywhere else. They inform our sense of place, and by extension, the pride with which we call it home. The allure of Mardi Gras—perhaps the most elaborate of productions, typically spanning six to eight weeks—is largely within its emboldening of personal alchemy. Not only is it encouraged—and at times required—to don a costume, but the custom celebrates the freedom to shed your inhibitions and become someone, or something, else—if only temporarily. From the balls and parades of Carnival season in New Orleans to the courir de Mardi Gras processions held on the rural Cajun prairies, performance is an essential element of the festivities.

Louisiana has been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in more ways than one, including within the performing arts sector. Even before the pandemic, the industry has always been a precarious entity; performers and crew members are usually contract workers, and venues and organizations tend to operate along thin profit margins with limited reserves. Production seasons and show schedules are often planned far in advance, and can be massive logistical undertakings that require the coordinated effort of many different managers, artists, and crew to pull off. Besides being difficult to reschedule, the act of a performance involves a shared, communal experience that isn’t possible to execute within the current confines of the pandemic. Additionally, because gig money is often not enough to live on by itself, many performers hold other jobs within the hospitality or service industries and have thus been doubly financially impacted by the shutdown.

Here, the performing arts are woven into our collective cultural identity in ways more permanent and prominent than anywhere else. They inform our sense of place, and by extension, the pride with which we call it home.

With no end to the pandemic or government relief in sight for the near future, at least, venues and organizations are already seeing the ramifications of remaining in a state of prolonged limbo. Workers in the performing arts sector must rely on unemployment or find another source of income, arts budgets for the upcoming year are on the chopping block, and historic venues are at risk of closing permanently. Gasa Gasa and d.b.a, two independent New Orleans music venues, are up for sale. Opera singers who normally perform under Opéra Louisiane are traveling to Europe to find work. As the upcoming season approaches, and Louisiana remains in Phase 2 of reopening, a timeline for resuming full capacity productions remains unclear.

Still, as a society we’ve seen, again and again, that the arts are resilient. Given our region’s experience with Hurricane Katrina, performers and organizations here are especially adept at brainstorming innovative solutions—which at the present moment includes exploring the virtual landscape as a distribution platform, reinventing business models, and re-thinking the anatomy of a performance.

When our beloved festival season was first put on hold in the spring, organizers rolled with the punches to make the best of a bad situation. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival pivoted quickly to promote a “Jazz Festing in Place” campaign, while Lafayette’s Festival International de Louisiane put on an entirely virtual three-day fest. When it became clear that New Orleans’ annual Voodoo Music and Arts Experience would not happen this year, the festival’s organizers got creative and instead presented a drive-in concert series at the Lakefront Arena in July. The lineup of powerhouse local talent included The Revivalists, Tank and the Bangas, and Galactic; all three dates sold out of the two-hundred-and-fifty available car passes. In August, the band members of Galactic, who own Tipitina’s, launched “Tipitina’s.TV,” a six-week online streaming series featuring new, taped performances by local musicians in the legendary club. The ticketed webcasts are the newest initiative to save the famed Big Easy venue from shuttering altogether as it faces an uncertain future.

Along with music venues, local theatre companies are embracing technology as a new medium due to an abrupt end to their 2020 season. Le Petit Théâtre Du Vieux Carré, New Orleans’ most historic playhouse, is producing a radio play series with three installments thus far. Similarly, The NOLA Project—an ensemble theatre company in the city—will release “podplays” this fall until its next staged production in 2021. For its season opening program, Shifting Gears, Opéra Louisiane is moving outside and bringing the ultra-traditional art form to the public in a series of free hour-long serenades by masked singers. The company is also experimenting with its casting format by conducting a “Fantasy Opera Draft,” allowing fans to vote on their picks for the coveted roles in The Barber of Seville, which will be broadcast virtually in October. “We have to pursue it with a long-term mindset,” said General Director Leanne Clement. “We’re going to need these options for the next two years, or beyond that. To me, that means reworking not just our initial offerings, our performances, but also reworking how our organization is focused. The challenge with keeping these kinds of events sustainable is to not only change the event itself, but to change the system that supports it. We recognize that in order to sustain the arts, the base has to be broader.”

Photo courtesy of the Manship Theatre.

Beloved Baton Rouge venue, The Manship Theatre hasn’t held live performances since the beginning of the pandemic, finding the cost of hosting to not be worth the potential revenue brought in by reduced audiences required by social-distancing requirements.

For Clare Cook, the founder of Basin Arts, a Lafayette creative incubator that emphasizes dance and the visual arts, the answer lies within community partnerships. Instead of going virtual this fall, Basin Arts is collaborating with Downtown Lafayette to use the sprawling stage at Parc International as an outdoor studio space for dancers to conduct classes and train.

“I also see this as an opportunity, because we can keep our local community in this bed of creative energy,” said Cook. While dancers normally flock to bigger cities with more opportunities to advance their craft, the pandemic has forced many to return to their roots. Cook believes their talent can be harnessed as a force for good. “Why not mobilize the creative energy of the people who are connected to this place and returning home, even if it’s only temporarily, to show our community what the next level looks like in terms of professional artistry or creative collaboration? Let’s mobilize the amazing artists who are sharing space and time in our community right now, because they are the vessel to help the greater world understand human experience. Now more than ever, artists are necessary.”

The crux of the virtual landscape is that while it is a practical alternative to live performances, it rarely surpasses that—serving as merely a substitute for the real thing. As technology expands organizations’ abilities to connect with new audiences, local groups also find themselves competing with larger, nationally-backed institutions for attention, especially as many audiences start to tune out due to the over-saturation of virtual events.

Victoria Heath

Though many in the performance realm have come up with innovative ways to distribute their art via the virtual landscape, it is becoming more and more evident that this substitute will never quite add up to the real thing—experience and revenue-wise.

For the 325-seat Manship Theatre in Baton Rouge, holding a show at a diminished capacity in the already small-scale venue will rarely cover the cost to host it. “We didn’t think we’d still be here at the end of August,” said John Kaufman, the venue’s Director of Marketing and Programming. “We thought we would be able to do at least live music at a diminished capacity, but we’re still not able to.” They will continue to screen films through the end of the year and are hoping to resume shows in January.

“Not having a season was not an option for us, because so much of organization depends on the sponsors, and—you know—on making money. That’s the only way we function as an organization,” said Clayton Shelvin, who serves as the Performing Arts Director for the Acadiana Center for the Arts. In Lafayette, the arts are the second largest economic driver behind oil and gas, and as the ACA faces potentially steep budget cuts to its public funding, the center’s predicament—like so many others—illustrates how the long-term consequences of the pandemic reverberate beyond the absence of live entertainment alone, and are far more insidious. Less public funding combined with the loss in revenue normally generated from ticket sales doesn’t just mean fewer performances—dwindling resources drastically hinders ACA’s ability to do community outreach. Besides operating a venue space and gallery, ACA also functions as an arts council, offering culturally enriching programs and arts education for children who otherwise may not be exposed to the arts. At stake are not only the futures of today’s gifted entertainers and performers, but of an entire generation; the impact on emerging artists, who may not find opportunities or support to pursue creative work as a result, cannot be overstated.

This is not a question of if the performing arts will survive, but what they will look like in a post-pandemic world. How far-reaching will the damage be? Who will recover? More importantly, who will not? What will this mean for them, and in turn, us?

Raegan Labat

Clare Cook, Artistic Director of Basin Arts Dance Collective, offers a positive outlook on the current situation. "I see this as an opportunity, because we can keep our local community in this bed of creative energy."

When the dust does eventually settle and companies can open their doors again, companies will face two unique challenges, said A.J. Allegra, the artistic director at The NOLA Project. With the pressing need to recoup lost revenue, they will have to stage shows that are cost-effective to produce, popular enough to sell tickets, and will appease a base of affluent, oft-older and majority white donors. “That first show has to try and thread a virtually impossible needle,” Allegra said. It not only has to entice people to spend money on entertainment when that will not be their first priority, but it also has to ensure people feel safe enough to attend and reinstate their confidence. “As much as we, as administrators, want the arts to be virtually free for all, they do come with a cost and unfortunately that cost, as it’s prioritized by the American populace, is considered an excess, a luxury item.”

As an organization with a low overhead and small staff, The NOLA Project is lucky in that it can weather the storm (“we’re like artistic cockroaches,”) Allegra said, but not every institution will be able to pull itself up by the bootstraps because some are simply too heavy. Allegra predicts mid-size companies—those with budgets between two and ten million—will be the ones to suffer most, will be the ones forced to close or consolidate with other bankrupt organizations.

This is not a question of if the performing arts will survive, but what they will look like in a post-pandemic world. How far-reaching will the damage be? Who will recover? More importantly, who will not? What will this mean for them, and in turn, us?

“You know, the arts are constantly at odds with our funding sources when we’re trying to expand access in order to reach more people,” Allegra said. “Louisiana is a very poor state. So, the arts have to be accessible to those below the poverty level, and when we’re faced with such a dire economic crisis, we’re forced to do so much of our programming in a for-profit model of reliance on ticket sales and asking the wealthy for money. You’re going to see a decline in diversity and a decline in access. And that’s the worst thing of all, because when you decrease access, then your art becomes elitist.” As an artistic director, Allegra’s job entails creating something stunning out of nothing, to flip the script on its head, he said. To say the industry itself can do the same, to persevere and emerge better than ever, is to deny the potent reality it faces. “The arts are in serious danger.”

In the opening line to her iconic 1969 essay “The White Album,” writer Joan Didion offered a simple and undeniable truth: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Our storytellers and culture bearers help us to grapple with the spectrum of human emotion, to participate in an exchange of beauty, and to remember the joie de vivre. When all is said and done, we will need to remember.